10.14.2022

Joseph Magliaro and Matt Lifson

The Ludwig Series and Fade In

Joseph Magliaro The Ludwig Series (Parergon to a Domestic Symphony)

Every thing is always something else. As confusing as this initially seems, it quickly becomes clear. Take, for example, a grid, the classic modernist tabula rasa. Plot one point, then another. Now, something begins to happen. No matter how remotely placed or how far apart in space, a sense of possibility arises between them, joining them together into something new: a line. It’s a particularly strange quality since there’s nothing inherent to either point that connects it to the other. Instead, the potential to be something else — to become no longer a singular point but a part of a line — emerges from the shift in context and bubbles up between the two. Scale up and this potential remains, from point to line to plane to prism.

It is also present as a motivating principle in Joseph Magliaro’s work. Each piece is formally simple, but existentially slippery. Though it’s easy to describe what the various pieces in the Ludwig series are made of (primarily planks of MDF, laminated in shades of cobalt, green, and pink), determining what they are is a different matter entirely. Each piece simultaneously suggests multiple uses and identities, without settling on a single one. As Ludwig Low Table/Bookstand, 3 Leg (2021) titularly alludes to, different possibilities are evoked depending on orientation and context. When standing on three legs, the work resembles a table. Flipped upside down, however, it becomes a bookstand, with those same three legs acting as dividers.

Put differently, Magliaro’s works are easy to perceive but impossible to interpret. Like a drawing that resembles both a rabbit and a duck, made famous by philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein in his Philosophical Investigations, multiple possibilities are present, but none is definitive. Each piece is discrete as an object but entirely undetermined. Ludwig Parergon (Side Table/Lamp) (2021), for example, could be a side table, a lamp, a seat, a sculpture. In this way it even oscillates between a seemingly harder edged distinction, that of art vs. design. Though these pieces may be functional, the multiple uses they suggest serve to highlight their formal qualities, offering up the possibility of an aesthetic experience outside of utility. Oscillating between fixed identities and bringing into focus the bounds of context, they remain always open ended.

–Alec Recinos

Exhibition

October 14 – November 12, 2022

Opening Reception: October 14, 2022 6 – 9pm

October 14 – November 12, 2022

Opening Reception: October 14, 2022 6 – 9pm

Matt Lifson Fade In

In Matt Lifson’s Fade In at NOON Projects, Lifson explores the impact of film on queerness as both a personal investigation and a cultural critique. Lifson looks back to his identity-forming teen years and turns to our image culture to find a language for self-sense-making. The particular films don’t matter so much as the way Lifson pulled from the stew of mass media images floating in his memory, his personal exploration suggesting the viewer could do the same. In the gaps between seemingly disparate images laid atop one another, a narrative is suggested, left for the viewer to piece together.

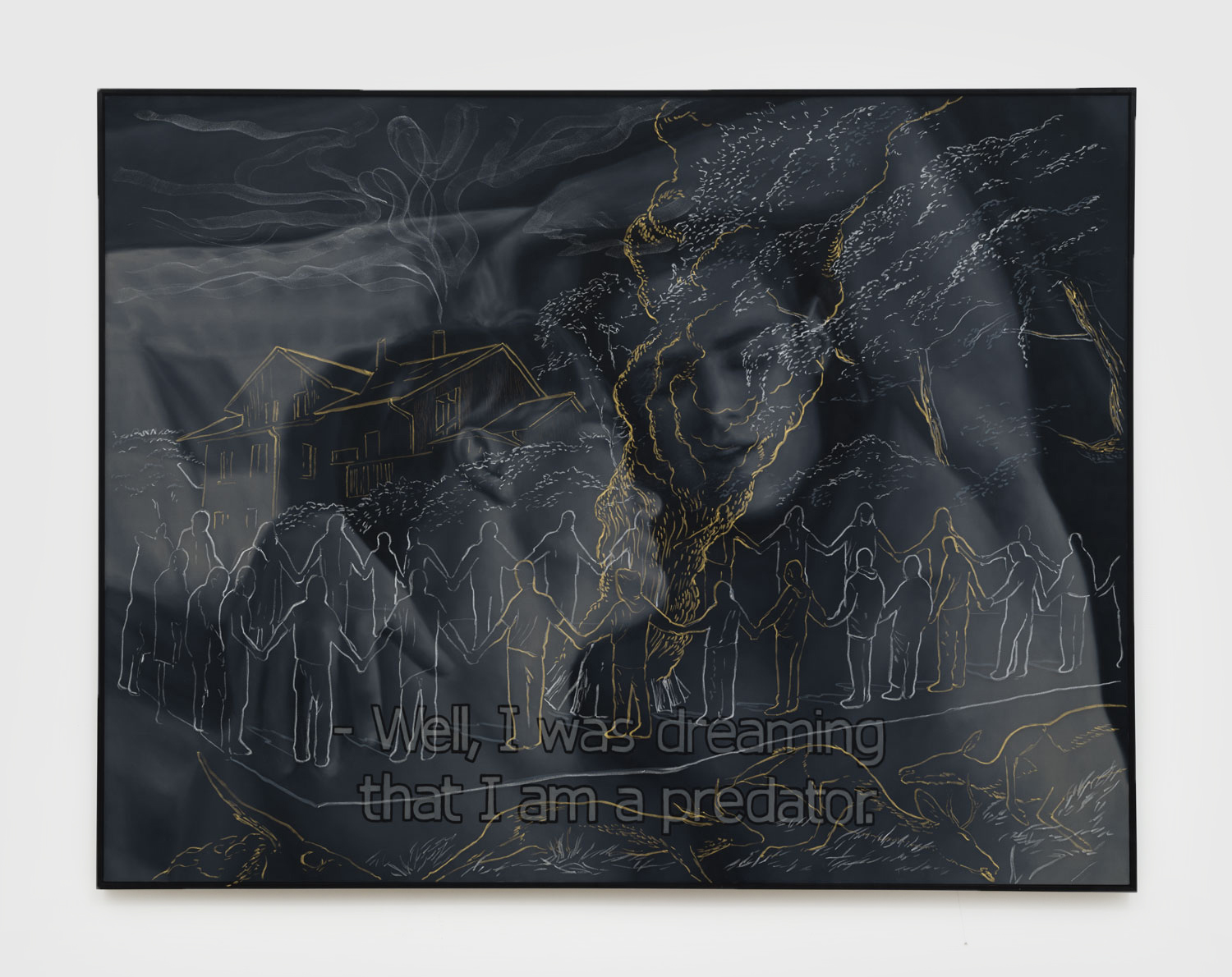

In both (Music Playing) and Hunter’s Dream are scenes of two male figures sharing intimacy, a perennial theme of Lifson’s work, although perhaps more sad than erotic here. The intimate scenes—taken from a Russian porn and the 1996 film White Squall—are overlaid with a layer of sheer black silk that hovers a half-inch in front of each of the two paintings with pastel drawings of suspenseful horror scenes. Viewing from the side has the effect of one image tearing away from the other and disappearing. Sketched onto the black silk, the horror film scenes suggest different kinds of danger. There is a horror in meeting a stranger from the internet, in becoming a person we were warned about, in becoming other, in being attracted to someone we might also like to become.

In Time Out three lonely figures stare out from their own corners of the painting into an empty space with the ghostly trace of the other two, like a jammed slide projector or 1990s music video, as if waiting for or searching for one another. To each other each figure is an other, never on the same plane despite being right there. There’s a musicality to these paintings, just like memories and fantasies become atmospheric in your mind. In the anchor piece of the show, S for mom, is another kind of interplay between surface and submerged. A rope in water moves like a body in space, shaped like the letter S for Lifson’s mother Susan. Is the rope an attempt to save? Did someone not make it?

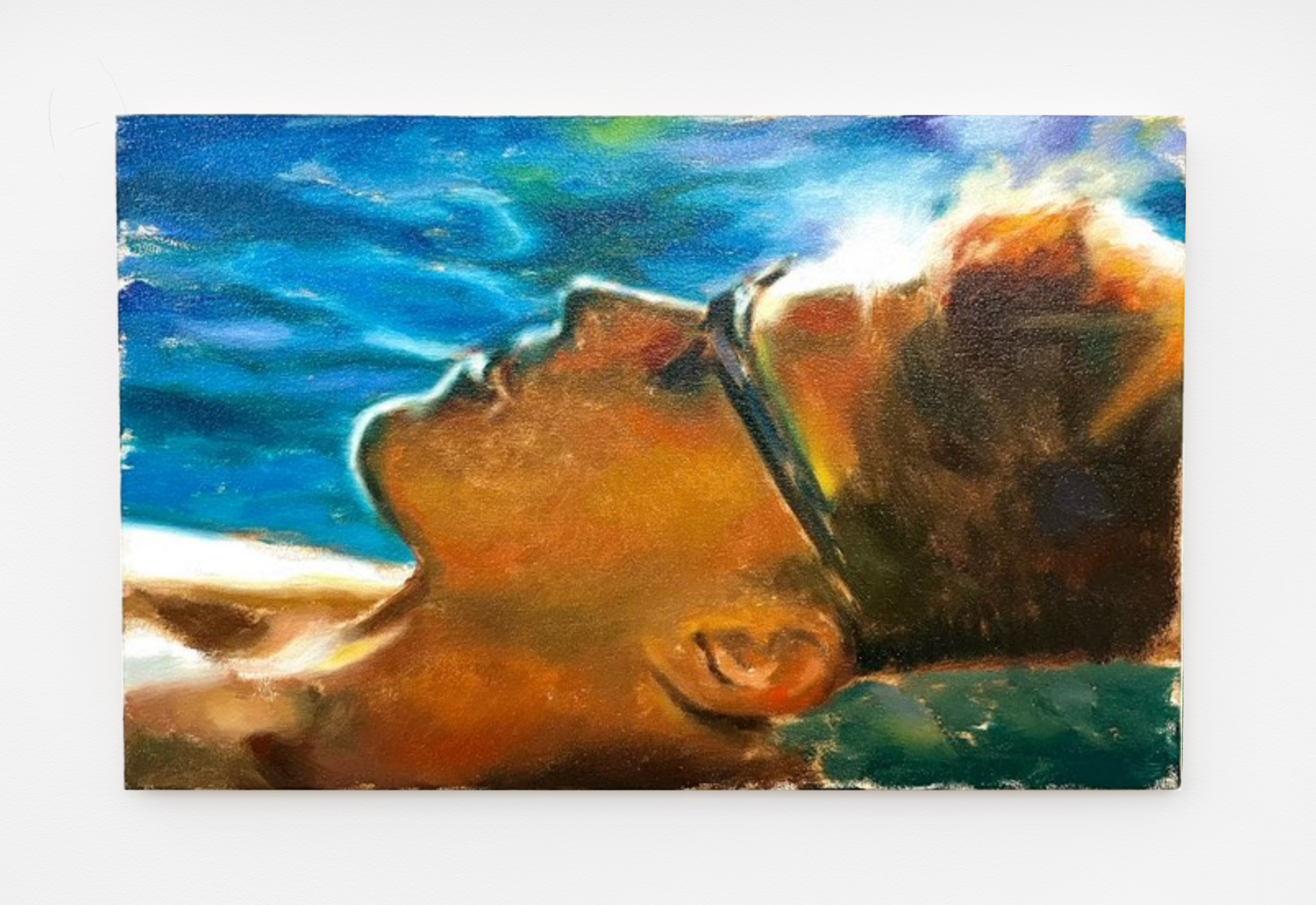

Echo and Me, Myself and I add color to the show in a grainy VHS hue. A boy is positioned horizontally, looking down contemplatively and in the other, looking up, relaxed, with sunglasses. Or are these sex scenes? We’re still in a filmic narrative here, the lyrical and dreamy on full display. The washy nostalgic figures are Lifson—and us—and the primordial soup of ocean waves and night sky become the erotic space for imagining a self.

–Stephen van Dyck

In Matt Lifson’s Fade In at NOON Projects, Lifson explores the impact of film on queerness as both a personal investigation and a cultural critique. Lifson looks back to his identity-forming teen years and turns to our image culture to find a language for self-sense-making. The particular films don’t matter so much as the way Lifson pulled from the stew of mass media images floating in his memory, his personal exploration suggesting the viewer could do the same. In the gaps between seemingly disparate images laid atop one another, a narrative is suggested, left for the viewer to piece together.

In both (Music Playing) and Hunter’s Dream are scenes of two male figures sharing intimacy, a perennial theme of Lifson’s work, although perhaps more sad than erotic here. The intimate scenes—taken from a Russian porn and the 1996 film White Squall—are overlaid with a layer of sheer black silk that hovers a half-inch in front of each of the two paintings with pastel drawings of suspenseful horror scenes. Viewing from the side has the effect of one image tearing away from the other and disappearing. Sketched onto the black silk, the horror film scenes suggest different kinds of danger. There is a horror in meeting a stranger from the internet, in becoming a person we were warned about, in becoming other, in being attracted to someone we might also like to become.

In Time Out three lonely figures stare out from their own corners of the painting into an empty space with the ghostly trace of the other two, like a jammed slide projector or 1990s music video, as if waiting for or searching for one another. To each other each figure is an other, never on the same plane despite being right there. There’s a musicality to these paintings, just like memories and fantasies become atmospheric in your mind. In the anchor piece of the show, S for mom, is another kind of interplay between surface and submerged. A rope in water moves like a body in space, shaped like the letter S for Lifson’s mother Susan. Is the rope an attempt to save? Did someone not make it?

Echo and Me, Myself and I add color to the show in a grainy VHS hue. A boy is positioned horizontally, looking down contemplatively and in the other, looking up, relaxed, with sunglasses. Or are these sex scenes? We’re still in a filmic narrative here, the lyrical and dreamy on full display. The washy nostalgic figures are Lifson—and us—and the primordial soup of ocean waves and night sky become the erotic space for imagining a self.

–Stephen van Dyck