January 2025

![]()

Between Presence and Absence:

Sayantan Mukhopadhyay Interviews Jay Stern

Curator Sayantan Mukhopadhyay speaks with artist Jay Stern about Slow Opening, Stern’s exhibition currently on view at NOON Projects through February 8, 2025. Their conversation explores themes of eroticism, desire, and queerness—often evoked in the absence of the body—while also tracing artistic influences from Stern’s adopted home of Maine, including Marsden Hartley and Lois Dodd. Stern reflects on the intimate residue of objects, the shifting role of landscape in his work, and the idea of queerness as a process rather than a fixed state. Together, they consider the power of ambiguity, memory, and the act of revisiting an image, a place, or a moment.

Sayantan Mukhopadhyay: Talk to me about the title, Slow Opening.

Jay Stern: Initially, I wanted to make a love-oriented show about romance and collaboration; connection and partnership. Instead of trying to make a show about my connection to everything around me in a romantic or sensual sense, the work evolved into an exploration of my own body and orientation to those themes. The closing and retracting of vulnerability had me thinking about the breath— this breathing mechanism that also speaks to the repetitive nature of the domestic experience.

Installation image of Slow Opening, by Jay Stern

NOON Projects, December 2025 - February 2025

Image by Josh Schaedel

NOON Projects, December 2025 - February 2025

Image by Josh Schaedel

SM: I think that there's something beautiful about the form of the verb that you've used. It's a gerund, which means it is in process. There’s a temporal element. We are often hellbent on moments of crystallization, but queer theory has taught us so much about process. Jose Esteban Muñoz has said queer politics has to exist towards a horizon: it has to move us forward; there has to be momentum.

There's an eroticism in the title. We've talked a lot about the place of eroticism, desire, and sexuality but in the absence of the body. I know that's very important for you. Can you talk to me a little bit about that?

JS: Yes. I think because I am not always using the body in my work, I have to find other ways to represent my experience. Sex is an interesting theme within gay culture because I do believe sexual desire can be portrayed in ways that don’t always need the body to function or tell a story. In the absence of the body, it feels like there are some real challenges but also vast opportunities to “portray”. Often my best work emits a similar vibe to that of a portrait, but is built up of different parts and speaks to the arrival and journey within a destination fueled by desire.

The queer figurative movement has also allowed me to question how we define queerness, using other attributes to communicate, and how we can define queer lenses within a work of art without the body. Perhaps we can’t? I suppose that’s the question I am hoping to answer.

SM: That's a fantastic question.

You called it a movement but I don't think It has been historicized as such yet by art historians. I know for a fact that 20 years from now, there are going to be little PhD students who are going to look back at this moment in American painting to study it.

JS: Can you share some thoughts on the body and its representation in figuration currently?

SM: I think the body is of course incredibly powerful. I think the reason why artists like Salman Toor, Doron Langberg and Christina Quarles have arisen together in a moment is entangled with the #MeToo movement, Black Lives Matter, the global pandemic– the havoc it has wrought on our sense of interpersonal connection. I'm unsurprised that the body has become a focus because it is a locus for experience, and of course experiences of difference.

Yet your paintings show that perception transcends the body. There’s something deeply sexy about the plate and fork in “Dinner at Michael’s.” It gestures to a body now absent. I think about your laundry paintings, too, because clothes have an intimate relationship with the wearer, but we don't know where that wearer is in your frame. The clothes are the residue of our lives.

Jay Stern

Dinner at Michael’s (Fork and Plate), 2024

Oil on Panel

19 x 29 1/2 x 1 3/4 in. |48.3 x 74.9 x 4.4 cm

Image by Josh Schaedel

JS: I love that, thank you. The residue of our lives. I feel like residue is something as the artist I have to add carefully that is only really seen or felt if someone is actually looking. Like a lens added to something to slightly skew or shift a perspective, or hint to a gestural form that feels fleeting.

SM: I like how you’re talking about the lens. Can you tell me about your relationship to the camera? I know that it was probably perhaps more present in some of your earlier work. What's your relationship now?

JS: On a practical level, I have no other choice but to use the lens to document and bring the source of a thing to the forefront. The lens is also used to abstract, layer, and bring the viewer (and myself) further away from the thing I am trying to present. This can either feel like hammering a bent nail and sometimes feels like warm butter sliding off a knife, just depends. Nonetheless, I rely on the lens and its ability to hinder the source from being too loud and also still allowing some of that source image or images to make their presence known.

SM: The residue.

JS: Yes, the word residue is really right because it speaks to time and history, which feel important in my work. I think my tabletop paintings hold both loss and a care for history or resurfacing at the same time.

SM: I think of “Summer Symphony” and what is really evocative to me in this image is that the cups and the mason jar with the water–all of these have traces of the people who've touched them.

Jay Stern

Summer Symphony, 2024

Oil on Canvas

45 x 40 x 1 3/4 in. | 114.3 x 101.6 x 4.4 cm

Image by Josh Schaedel

JS: Ya, but those people are gone. Or, are they about to enter the painting? Or, does their timing matter? I feel like this work is “post-human,” hopeful but quiet.

SM: Your work has always been suffused with nostalgia for me. There’s something so beautiful about what we've left behind in a moment. That's not to say we won't come back to it. I think that's the hope that's written into your work, I think that it’s really important that it can be re-entered.

JS: I’m happy you think so too. I like to think about them as quiet but active places and being able to re-enter creates hope in the work is interesting. I don’t think I ever want to let go of something 100%, which speaks to that option of re-entry. It's about reality and the unreal, this dancing between the two is pretty important I think.

SM: This is definitely one of my favorite things about your work. There’s an example of an older work where you were really messing with space. You collaged multiple source images from photos, making it quite clear to the viewer what you were doing. But then I think that has been a lot more subtle in your work. You enter your space as though on unsteady ground.

You and I have talked a lot about Sarah Ahmed and her conception of queer phenomenology. A queer orientation means nothing is offered to you head-on. It is angled; it is indirect; it comes from askance. You have to look once, twice, three times before you’ve read the space.

JS: Like cruising or the queer gaze. It’s an interaction about recognition.

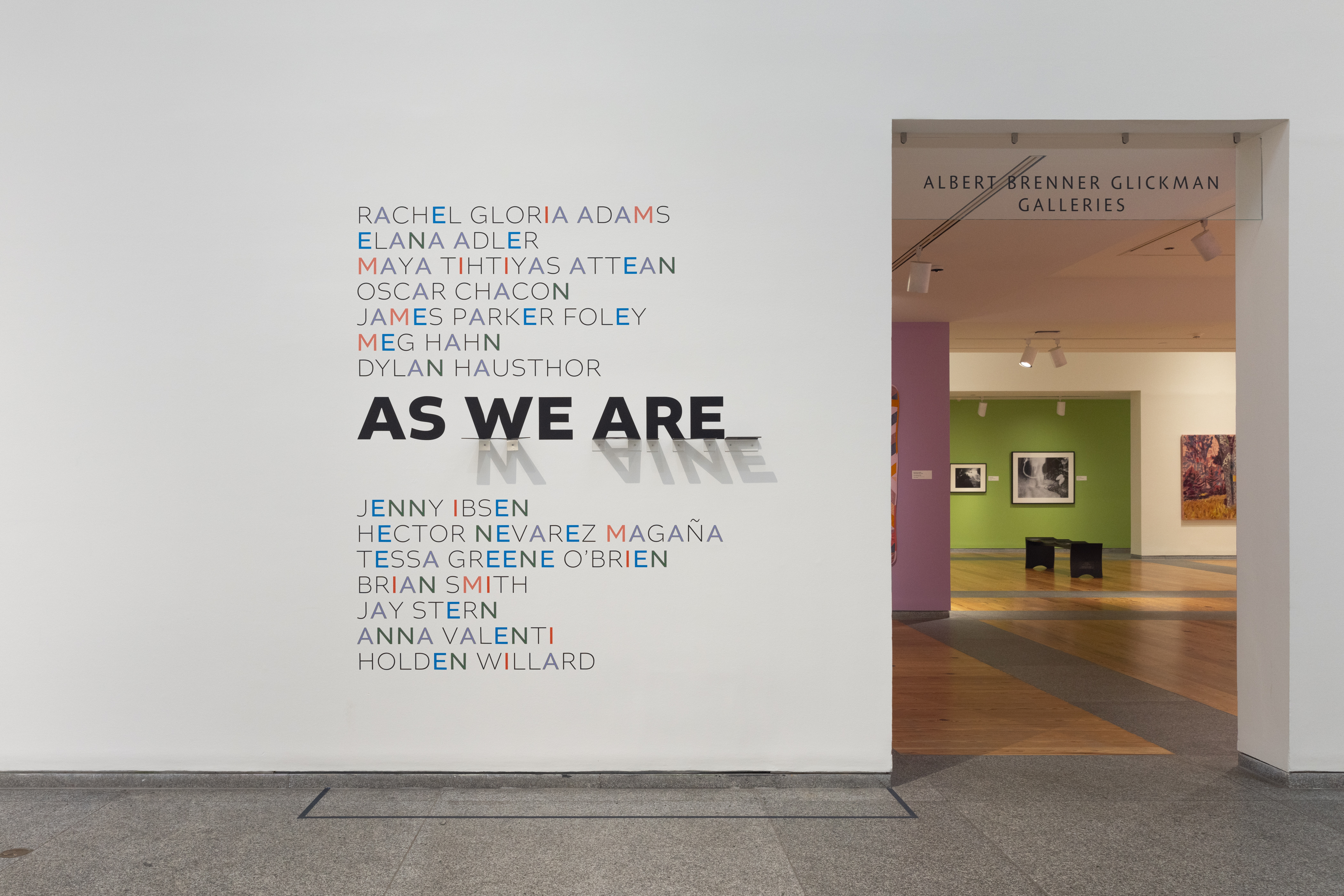

Installation images of As We Are

Portland Museum of Art, Portland, Maine

Images by Abby Lank

Portland Museum of Art, Portland, Maine

Images by Abby Lank

SM: And it's furtive. In one of the works in the show “As We Are” here at the Portland Museum of Art, you have painted an oblique view. I still have to look at it closely to make sense of it. It's that invitation and re-invitation for viewers where you're not trying to give everyone everything all at once.

JS: That’s nice to hear. I’m aware that my work is made out of an effort to secure or immortalize. Due to the nature of that pursuit, the connection to the visual object is so essential in surfacing a familiarity but also an abstraction. This interplay helps in that entry/re-entry, it’s enough of the unreal that additional visits help solidify. Like seeing a work of art in a museum and then finding it at another museum years later. It’s refreshing, it's reliable, and it’s a relationship. The same with a song you haven’t heard in a long while, it situates you, puts you in your own history. The shape-shift, the desire for repetition but the understanding that the cycle continues.

I love this from Monet, “The illusion of an endless whole, a wave with no horizon and no shore.” Everything is constant but also no horizon in sight. Feels a bit like the queer experience in that we are always morphing and changing but we don’t ever have to suffice to a destination.

SM: The rules have been undone for us and that’s freeing.

JS: Yes, I feel grateful to live an undone life. I think the idea of “opening” exists in the undoing.

SM: I think that that is a nod to the fact that I think a lot of queer politics involves breaking things before they can be repaired because systems were never created for our survival. So it's about kind of breaking what's given to us and then reconstituting it with the fragments. I think that's what you're maybe doing in your work.

JS: Correct, the plate painting does this the best. That one came quickly, usually I have to break things a lot more times in my work for something exciting to occur but that one slid off my brush.

SM: You are four years deep into your move to Maine. That's something that we share as recent arrivals. What role does Maine as a place have for you now?

JS: Good question because it’s quickly evolving and there’s honestly too much to say on this subject. I have so much respect for the artists who have been here before me and what they chose or found here. I like living in a place that sort of scares me and keeps me on my toes… knowing full well that it will continuously provide in a visual sense, but also knowing that I will have to decide what to bite off. I’m finally feeling like I have a clear understanding of what is mine to take and how I can support it in the making of an image. I am also curious about how I can take from the iconography of the area in painting. “Desire Destination” is a good example of this where I took a bunch of Neil Welliver canoe paintings and uh, took them and plopped them in a painting, directionless. Have we talked about this?

SM: No.

JS: Welliver painted people in canoes, usually pairs of people and after studying them, I felt they were holding too much easeful joy. I am mostly a happy person but these works I could not relate to, or I felt confused about their direction. So I stripped the canoes of their paddles and people and collaged them together in a scene that had them going every which way. It’s like Hartley with the seagull, although I would never skew anything Hartley ever did, Ha ha.

Jay Stern

Desire Destination, 2024

Oil on Canvas

48 x 48 x 1 3/4 in. | 121.9 x 121.9 x 4.4 cm

Image by Josh Schaedel

Desire Destination, 2024

Oil on Canvas

48 x 48 x 1 3/4 in. | 121.9 x 121.9 x 4.4 cm

Image by Josh Schaedel

SM: I didn't even notice that there were no paddles. My colleague here at the PMA, Ramey Mize, who is our associate curator of American art, has encouraged me to think about the place of canoes in the history of settler American landscape painting. The canoe is often painted into water scenes with no recognition for the histories of colonization that allowed it to become a part of our visual lexicon.

I love that in your painting that they're you've ridded it of the thing that gives the canoe its direction: no oar, no paddle. We're sort of flailing.

JS: Haha, yes we are. It’s really fun if you can allow it. I am working on it.

SM: So I have to ask about Lois Dodd.

JS: Yes, you mean, the queen? Lois really helped create a glossary for me visually in Maine. Her work feels both effortless and that she took a journey to find what she painted. She helped me understand the static active and still ways that Maine’s landscape visually operates, she is full of tricks and I think I can recognize them. I mean that with all due respect and therefore, I feel close to her work. I like that her work feels both voyeuristic and curious and very much clearly the thing she is hoping to present. It’s remarkable how so many of my peers in Maine and throughout feel inspired or a kinship to her. Her work feels unafraid yet sensitive.

Lois will always be in my back pocket but I think I have found a way to forge my own path. Similarly, my body in nature, just like her. Nature's vastness really does hug you sometimes in Maine but often it's overwhelming which is why I have started to collage and sprinkle man-made objects into these landscape paintings. Do you find nature comforting?

Images by Chloe Gilstrap of Likeness Studios

Hope, Maine 2024

Hope, Maine 2024

SM: It’s something I think about a lot now that I live in Maine, the most rural state in the country after Vermont. In LA, which is where I spent the majority of my adult years up until now, I find there's a really beautiful integration of nature into city life. You have everything a global city has to offer, in addition to the mountains and the beach.

That was a really incredible balance for me that worked. I find the quiet of Maine to be somewhat daunting at times. In that quietude, you find a lot of loneliness. We have a lot of crutches available to us in more urban landscapes so a place like Maine really challenges you to find that self-love that everyone in LA is talking about. You really have to practice it in Maine.

JS: That does speak to the title of my show. There can be a sense of emptiness in the opening too that if you play it just right can either feel well, lonely, or a practice.

SM: Yes, “Slow Opening.” The vulnerability of opening yourself up to love what's inside, too.

A lot of queer painters rely on figures to express a social form of love, but for your work there is an intimacy of the self. It’s what is so powerful about your work at this moment.

JS: Thank you. That does relate to Lois Dodd, but I must bring in my favorite gay uncle, Marsden Hartley.

SM: Yes. Oh my god, Marsden.

JS: He was lonely.

SM: Yeah, you can see it in his work.

JS I'm okay if there's a little bit of sorrow in my paintings, or real emotion like I feel from him. The way his landscape paintings aren’t just landscapes but poems too. Makes me believe that the power of expression lives inside and needs to be released. Those paintings hold multitudes.

SM: I don't think I've ever, in all the months of knowing you now, have seen a work on paper and you have multiple drawings in the show. Can you tell me about that medium?

Jay Stern

Pool (Fire Island), 2024

Pencil and Charcoal on Cardboard (Framed)

8 x 6 1/2 in. | 20.3 x 16.5 cm

Image by Josh Schaedel

Pool (Fire Island), 2024

Pencil and Charcoal on Cardboard (Framed)

8 x 6 1/2 in. | 20.3 x 16.5 cm

Image by Josh Schaedel

JS: It’s developing. I actually had them hiding in a notebook and found them when selecting for this show and was like hmm? Someone even used the word draftsman for them, which I thought was nice.

SM: Yeah, they're like blueprints.

JS: Yeah, drawing has allowed me to break up space in a different way that feels almost more abstract. There's a different style of control that the brush and the pencil do not share that is fun for me to play with and pace is not the same between the two mediums. Matthew Wong is someone who inspires me in regards to how he broke up and understands how to read the landscape in a way I find kinship to, also like Milton Avery or Diebenkorn. There’s a bit more planning in the drawings because I make them all plein air.

I have a question for you. What’s your relationship to objects? You are someone who has moved around a lot and held many different lives, are objects something you hold close or are they a signifier of change? Do they breathe for you?

SM: You know, it's funny that you should ask that. I was just bemoaning the other day that in all my travels–which I did a lot of in my 20s–I didn’t collect many things. I was looking around my apartment, now in my mid-30s and perhaps wanting to feel more settled, and I found very few talismans of my past. I think when I was younger, I was worried about accumulating trash. Perhaps I’m more sentimental now but I’m sad I don’t have more souvenirs. The word souvenir of course comes from the French for “to remember.” But I like to think that just because I don’t have the objects doesn’t mean I don’t have memories.

JS: It’s interesting when an object is used to initiate a memory, but, I agree that you don’t need to have them to feel them. But the objects maybe just help you along.

SM: I now wear a lot of family heirlooms. A ring my mom was given by her best friend; a necklace made from my mom’s wedding jewelry.

JS: The physicality of jewelry must feel nice. Connects you to those people.

SM: Exactly exactly. I didn't feel the need for it before and then maybe this is a part of getting older.

JS: Can I read you a poem to close this out? It’s an excerpt from a poem by Lisel Mueller.

“I will not return to a universe of objects that don’t know each other,

as if islands were not the lost children of one great continent. The world

is flux, and light becomes what it touches, becomes water, lilies on water,

above and below water, becomes lilac and mauve and yellow

and white and cerulean lamps, small fists passing sunlight

so quickly to one another that it would take long, streaming hair inside my brush to catch it.

To paint the speed of light!”

SM: Beautiful. It's making me tear up.

JS: Oh, good. Before I started making the work for this show, a regular customer at a cafe in Maine I used to work at, dropped off a piece of paper and someone stashed it on the back table. This poem was written on the paper and I really like that life keeps giving me little clues.

_

January 2025

Sayantan Mukhopadhyay received his MA and PhD in Art History from UCLA. His current research interests include the politics of friendship, queer futures, and expressions of kinship in global contemporary art.