2.20–4.4.2026

Where there is Great Love there are always Great Miracles

David Shull

NOON Projects is honored to present "Where there is Great Love there are Always Great Miracles" by David Shull, the artist’s third exhibition with the gallery, opening February 20, 2026.

The phrase "Where there is great love there are always great miracles" appears on a stock photograph of a rose glistening with dew set within a faux-wood frame that the artist David Shull found discarded on the street. In keeping with the hallowed Hallmark tradition this maxim extends, the words fall apart the more you try to decipher their relationship to each other and to a world of meaning more generally. This is the typical dissolving structure of sentimentality—among love’s most debased articulations. As cipher, loaded value judgement, mode of relating, and form, sentimentality is also one of the throughlines of Shull’s expansive practice. Here, it unlocks an unlikely portal back into real feeling.

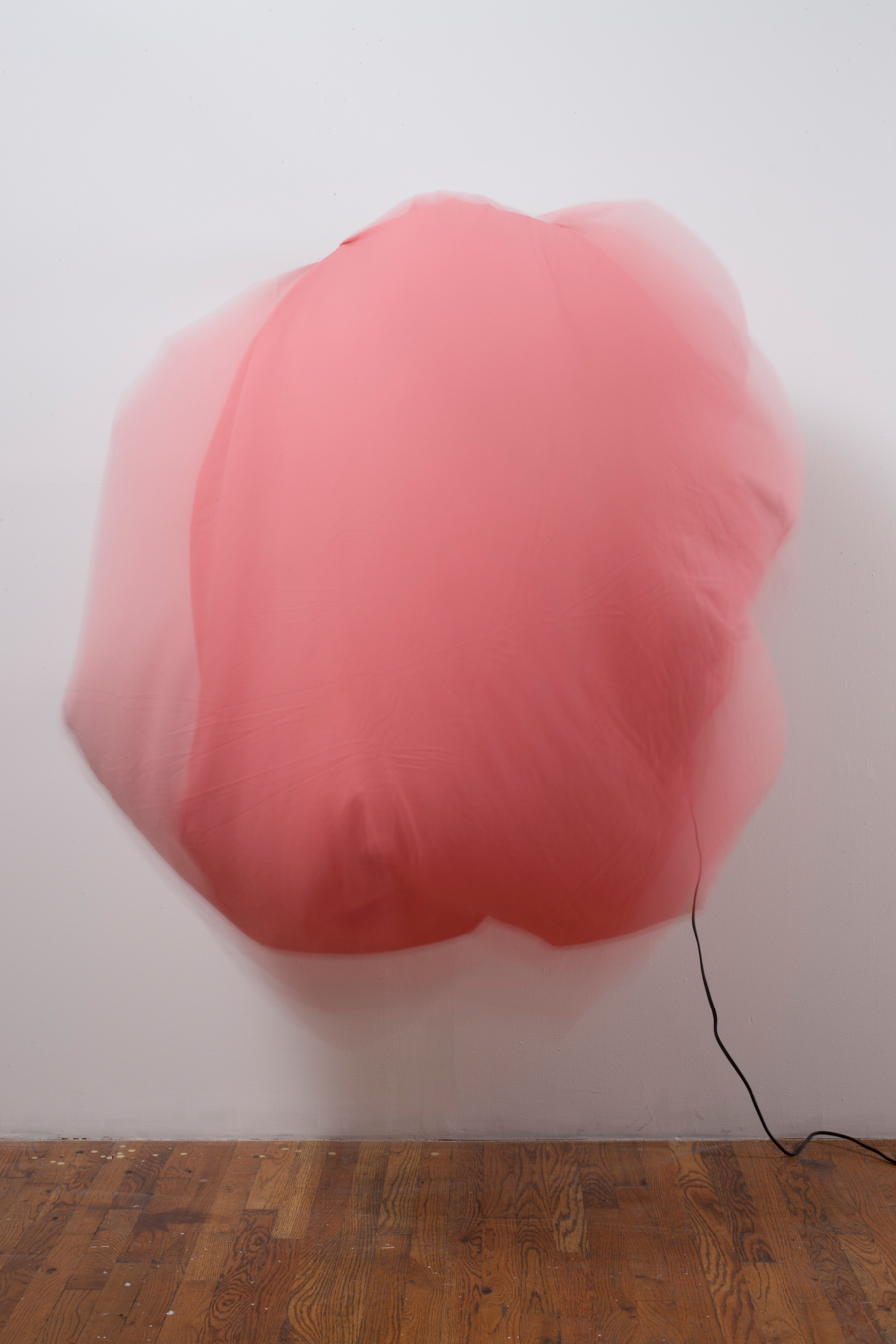

The sculptures, paintings, and drawings in this presentation offer a glimpse of a larger body of work over fifteen years in the making. While the form of an exhibition demands abridgement, the full sweep of this project remains a reverberating presence. Each piece in "Where there is great love . . ." is the result of a chain of responsive interventions: Shull may extend, distill, or recontextualize an element in response to its associative potential. Extrapolating the form of a gun from a particular configuration of blocky, shaped canvases in an early iteration of "Flesh Field" (2003), the artist made this association explicit by inscribing a pistol grip directly on the wall with Sharpie. The drawing "Road Romeo" (2003) is an inventive homage to the name of a bus that Shull spotted while working on an off-off-Bollywood production in Guyana. Struck by the schmaltzy designation, the artist concocted his own vision of romance in motion: a headboard (a decor flourish rattling with naughty subtext) on wheels, their rotation and velocity conveyed by Shull through spectral doubling and brisk, dizzying motion trails. Evocations run amok: the straightforwardly titled "Inflatable Bedsheet" (2012) is at turns swollen with hot air and abjectly flaccid, like some giant wad of bubble gum engorged and then collapsed, sans the decisive, sexy snap; made of vellum, a substrate derived from animal skins, the blush-colored folds of "Paper Vaginas"(2002) have devastatingly Freudian origins (an attempted Mother’s Day card).

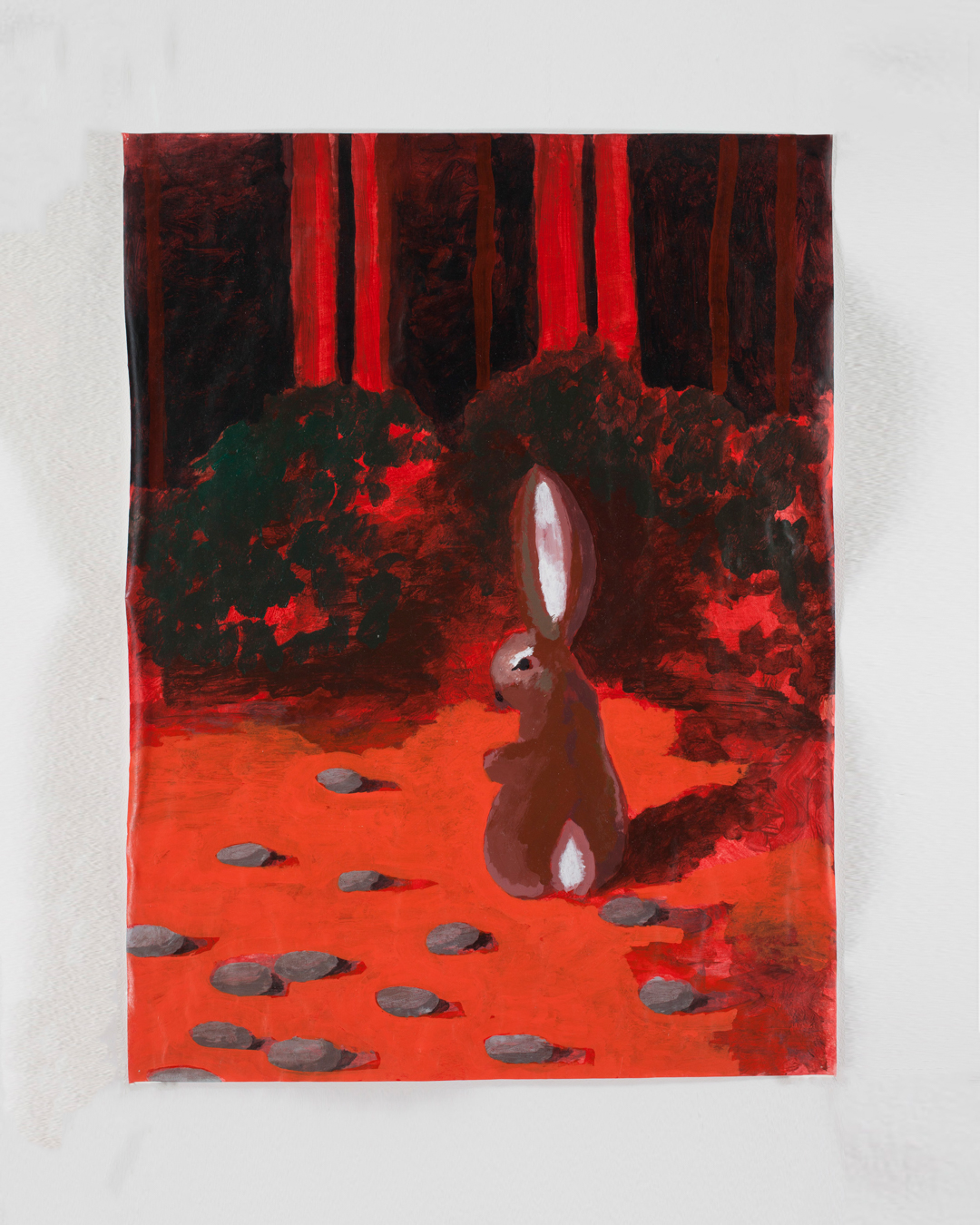

Together, Shull’s titles read like the table of contents from some pulpy romance, careening between campy sap and gentle perversion. A taste: "Flowers in the Wind" (2003); "Gushing Song of Love Over Watermelon" (2010); "Flesh Field"; "Dick Maze" (2003); and my personal favorite, a wink to untapped innuendos in the language of painting, "Wet on Wet"(2009). Likewise, the works are the bastard children of sincerity and cheekiness. Flowers, harvested for use as proxies for feeling, abound: printed on silky shoulder pads amputated from some since-misshappen, deflated garment; all a-bluster in swoopy, brushy acrylic strokes; flattened, de-natured, and reiterated ad nauseum on wallpaper; preserved in or maybe never-alive in a bell jar; festooning a grave in a photograph; as symbols in a rigged game of Tic-Tac-Toe. These are only a handful of the floral apparitions—their disparate forms linked by estrangement, to varying degrees, from the real, rooted thing.

Shull’s palette is shot through with what he calls “beige renditions of pinks.” In the visual language of sentiment, rosy reigns supreme. (Blush, coral, fuschia, so-called excesses of emotion—all are damned to the realm of girly shit, doomed to be trivialized ad nauseum by the terminally heartless.) A beige rendition of pink, though, tinges the hue with a dose of suburban banality; beige acting in a performance of pink, one color’s take on another. For this author at least, suburbia conjures a kind of desperate, constrictive affect, a slow-motion bludgeoning of the soul courtesy of the nuclear family. Shull’s associations are less violent. Among the threads linking his varied forms is the artist’s interest in the peculiar beauty of objects and moments so integrated into the fabric of mundane life that they rarely brush the surface of perception. So although grand themes like love and history charge each artwork, their less dramatic expressions—that is, their nuances—have a stronger hold here.

This extends to his approach to materials, which rhymes with certain aspects of the Minimalism of the 1960s and ’70s. Like artists such as Donald Judd and Dan Flavin, Shull often works with and in response to industrial matter, in many cases altering only the context in which it is presented. His are, in his words, “dumbed-down materials,” tweaked only to the extent that their construction or origins isn’t shrouded under some alienating veil of virtuosity. But he forgoes the canonical steel-plywood-lightbulbs (and self-serious fuckery) in favor of stuff from our world that skews more offbeat. A bedsheet, newsprint, bouquet wrapping paper, a pillow, wallpaper backing, Polaroid cartridges stacked in a helix and strung up like a mobile. The object from which the exhibition title is derived is embalmed in an epoxy cocktail known as “bar resin,” named for its frequent use protecting countertops from the collateral damage incurred in darkened, liquor-wet milieus. "Veteran" (2005) comprises three bolts of material linked together by carabiners, hanging like a wet towel on some bathroom hook. Called a “door skin,” this padded vinyl is another architectural swatch common to wining and dining joints, peeled from its sticky home and recast as sculpture.

As the title implies, "Where there is great love there are always great miracles." is, above all, a love story. The artist demarcates the span of time represented in this body of work in relation to falling in and out of infatuation (not necessarily in that order). Romantic love, yes, but also friendship—less glorified but equally sacred. That form mirrors Shull’s responsive approach to his work: friendship can have all the thrill of exchange without the transactional misery that comes along with the idea of possessing a person, with a sense of property. Of his friend Jack Doroshow, aka Flawless Sabrina, the patron saint of this series, Shull writes: “I think that I gave Jack as much as I received from him, but in truth, A. That would be impossible and B. I don’t think that we really wanted anything from each other.” The tale of how a legendary drag queen who came of age in 1960s New York and a much younger straight guy from California became close is beyond the scope, so to speak. Shull tells it better, anyway. The book that accompanies, distills, extends, and otherwise transforms the full scope of "Where there is great love . . ." is inscribed with Doroshow’s responses to the pages sent by the artist. Beyond synergistic electricity, Shull’s art and Doroshow’s poetic rejoinders share a rare sensibility: both possess all the wit of irony but remain utterly sincere, an unlikely affective alliance that hits like pushing on a bruise, or heartbreak.

— Sophia Larigakis

Exhibition

On View

February 20– April 4, 2026

Opening Reception:

February 20, 2026

6–9 pm

Performance:

SUPERCORN / DEAD DIVA DISCO

Curated by Ciriaco

March 5, 2026

7 PM

Free

NOON Projects

951 Chung King Road

Los Angeles

View Press Release

On View

February 20– April 4, 2026

Opening Reception:

February 20, 2026

6–9 pm

Performance:

SUPERCORN / DEAD DIVA DISCO

Curated by Ciriaco

March 5, 2026

7 PM

Free

NOON Projects

951 Chung King Road

Los Angeles

View Press Release